Works in Woodmere's Collection

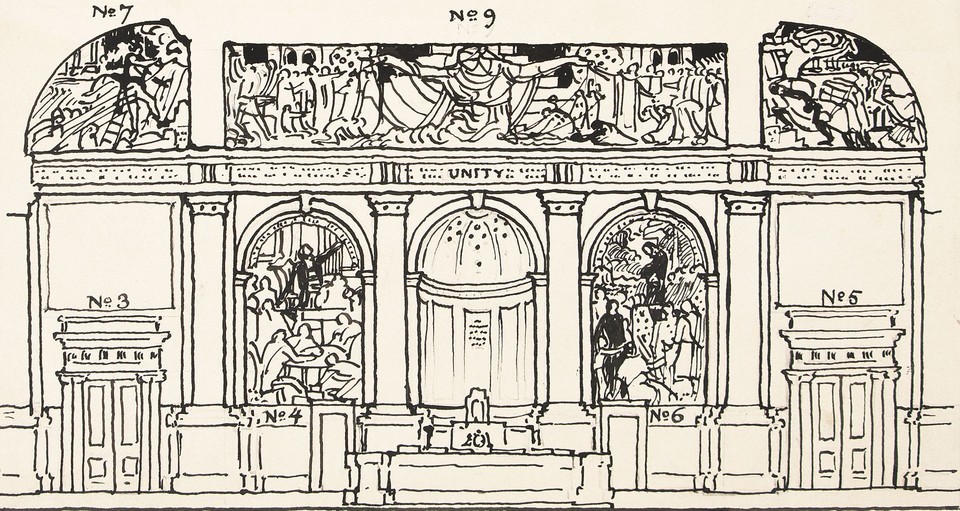

Study for General Meade and Pennsylvania Troops in Camp Before Gettysburg, 1963, for the mural series The Creation and Preservation of the Union, Senate Chamber, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for the widow, "Lincoln at Gettysburg, 1863" mural, from the series The Creation and Preservation of the Union, Senate Chamber, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

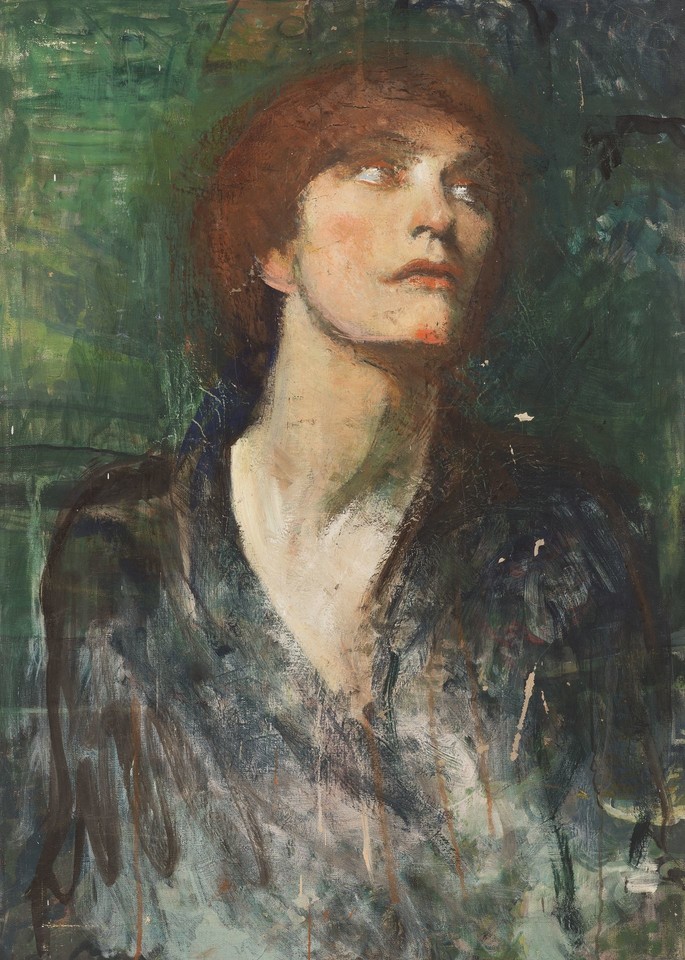

Study for the teacher (Mary Nixon, model), "Unity" mural, from the series The Creation and Preservation of the Union, Senate Chamber, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for the academic figure (Eugenie Fryer, model), "Unity" mural, from the series The Creation and Preservation of the Union, Senate Chamber, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

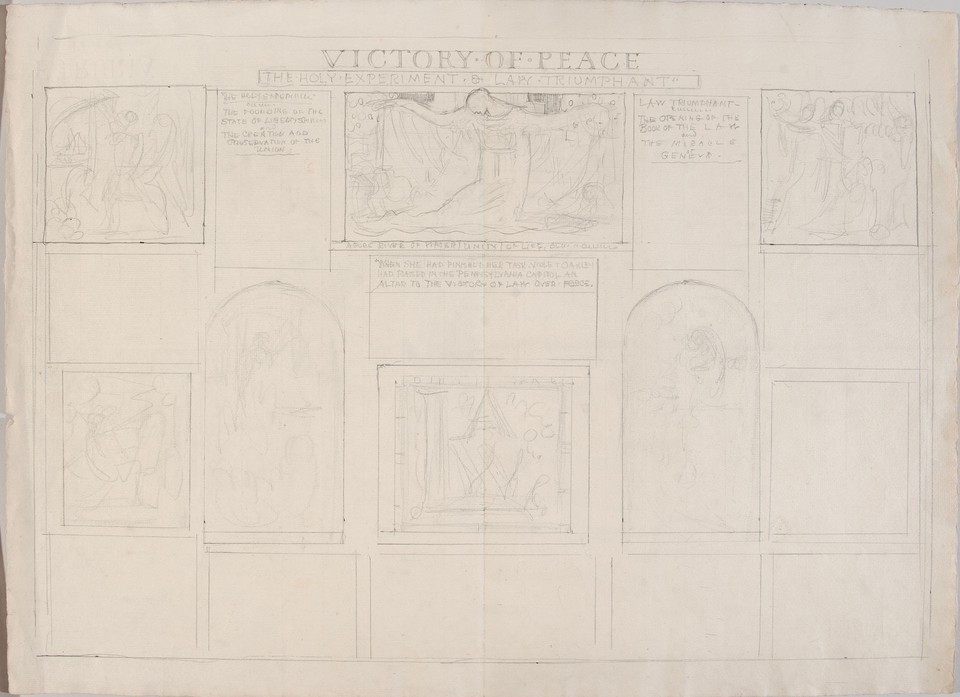

Illustration study for two-sided information sheet, "The Creation and Preservation of the Union"

Banners, Posters, and Brochures

View