Governor's Grand Executive Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol, "The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual"

To view Violet Oakley's Tour of the Capitol Murals in Harrisburg, 1955, please click here.

In 1902, Violet Oakley received a commission to paint murals in the Governor’s Grand Executive Reception Room of the Pennsylvania State Capitol. The mural layout called for a six-foot-high frieze above dark oak paneling along the seventy-two-foot walls, with two murals on either side of the sienna marble fireplaces centered on the twenty-seven-foot short walls. Capitol architect Joseph Miller Huston, whose unifying theme for the decoration of the Capitol was “The Founding of the State,” recommended that Oakley paint the history of colonization beginning with the “Greeks, Phoenicians, Romans” and ending with the arrival of Europeans in Pennsylvania.1 At the turn of the twentieth century, the term “colonization” was considered a euphemism for imperialism, a politically contentious issue in the United States following the annexation of the Philippines, Guam, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii. The Anti-Imperialist League, founded in Boston in 1898, had grown into a national movement supported by prominent cultural leaders such as Quaker social worker Jane Addams; writers Henry James, William Dean Howells, and Mark Twain; industrialist Andrew Carnegie; and former President Grover Cleveland, all of whom publicly condemned colonial expansion as a betrayal of the American principle of “the consent of the governed.” Oakley did not think colonization was an accurate representation of the founding of Pennsylvania by religious refugees. She informed Huston of her intention to trace the history of religious intolerance that led to William Penn’s “Holy Experiment” in North America, a polity based on the Quaker principles of nonviolence, equality, and liberty of conscience. “This,” she argued, “seems to be the true foundation of the State and of its power.”2

To prepare for the commission, Oakley went on a grand tour of Italy from March to September 1903, studying mural paintings in Rome, Florence, Siena, Perugia, Assisi, Padua, and Venice. She drew inspiration from the religious murals of Renaissance painter Vittore Carpaccio in the Confraternity of Saint George of the Dalmatians, the subject of a book by the English art critic John Ruskin.3 She spent the last month of her trip in London and Oxford researching the history of the Quakers and William Penn, which crystalized the theme of her mural program.

The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual is a frieze of thirteen episodes of religious strife during the English Reformation culminating in the Quaker exodus to Pennsylvania. The north wall chronicles the persecution of religious dissenters by the Church of Rome, the Church of England, and the Puritans. The historical turning point, symbolically placed where the viewer turns toward the west wall, is represented by scenes of the spiritual awakenings of George Fox, the founder of the Society of Friends (Quakerism), and his disciple William Penn. The east wall is a pictorial narrative of Penn’s religious conversion, his expulsion from Oxford, his imprisonment and trial, and his plan to establish a haven of religious liberty in the New World. The series concludes on the south wall with murals depicting Charles II granting the charter of Pennsylvania and William Penn on the bow of the ship Welcome approaching the Delaware River. By painting the prehistory of the founding of Pennsylvania without a single scene on American soil, Oakley avoided the imagery of colonization.

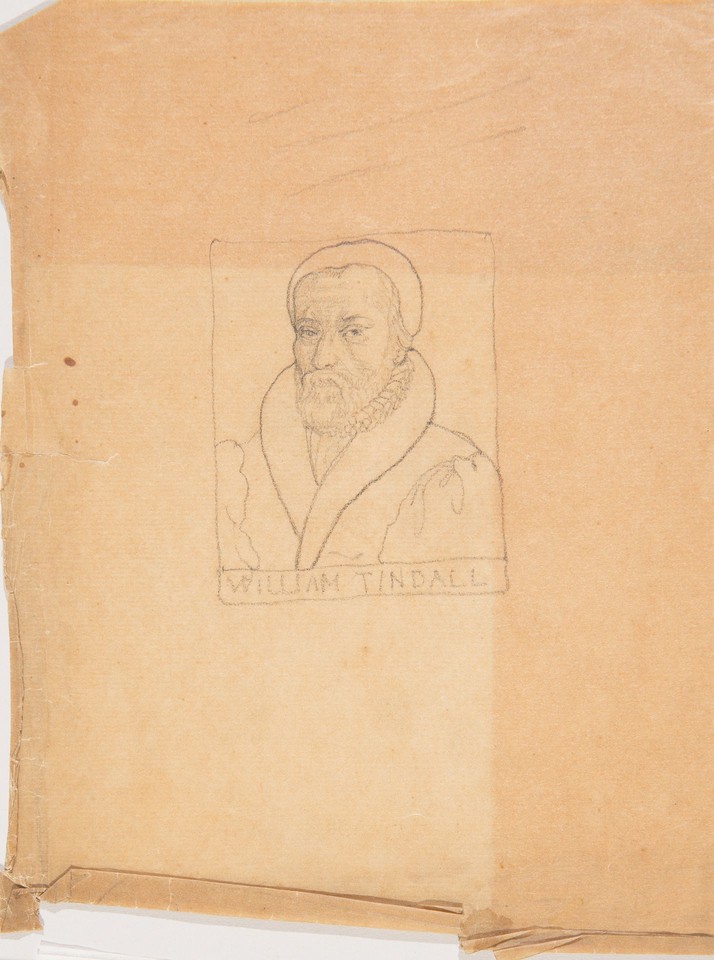

Nevertheless, a protest against the mural series erupted from a different direction. The Catholic Historical Society demanded the removal of the scenes depicting the Roman Catholic Church’s execution of William Tyndale and the subsequent burning of his English translations of the New Testament at Oxford, events they considered irrelevant to the founding of Pennsylvania and insulting to their community. Pennsylvania’s Catholics had not forgotten the violent attacks on Irish Catholics in the Philadelphia Riots of 1844, and the resurgence of nativist hostility toward Catholic immigrants arriving from Southern and Eastern European was a cause for concern.4 Stung by the accusation of prejudice, Oakley defended the historical validity of the controversial images, pointing out that she had also represented religious intolerance by the Anglican Church. Governor Samuel Pennypacker, a Quaker, supported the artist and the murals remained in place.

With the exception of the Catholic protest, The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual was considered a great success. When the first five panels were exhibited at the centennial celebration of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1905 with the luminaries of the art world in attendance, Oakley received a gold medal. “This award was greeted with prolonged and uproarious applause,” the North American reported, “and Miss Oakley, to whom the announcement was a surprise, was showered with azalea wreaths, and pelted with roses and carnation blossoms.”5 James B. Townsend, the critic of American Art News wrote that the murals were “really superior, strongly conceived and beautifully executed.”6 The Philadelphia Press judged the paintings “worthy of the great state for which the work is done,” adding that “if ever a politician’s soul can be elevated by his surroundings, we shall be in for the political millennium when the Governors of Pennsylvania have their being confronted by these splendid decorations.”7

1 The Pennsylvania Capitol: A Documentary History, vol. 2, Capitol Preservation Committee (Princeton: Heritage Studies, 1987) 352.

2 The Pennsylvania Capitol: A Documentary History, vol. 2, 352.

3 John Ruskin, St. Mark’s Rest: The Shrine of the Slaves, Being a Guide to the Principal Pictures by Victor Carpaccio in Venice (Orpington, England, 1877).

4 Zachary M. Schrag, “Nativists Riots of 1844,” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/nativist-riots-of-1844/

5 “Art Patrons and Painters Dine in Celebration of One-Hundredth Anniversary of the Academy of Fine Art,” The North American, February 24, 1905.

6 James Townsend, “Pennsylvania Academy Exhibition,” American Art News, January 1905.

7 “Some Contrasts and Miss Oakley,” Philadelphia Press, January 22, 1905.

Works in Woodmere's Collection

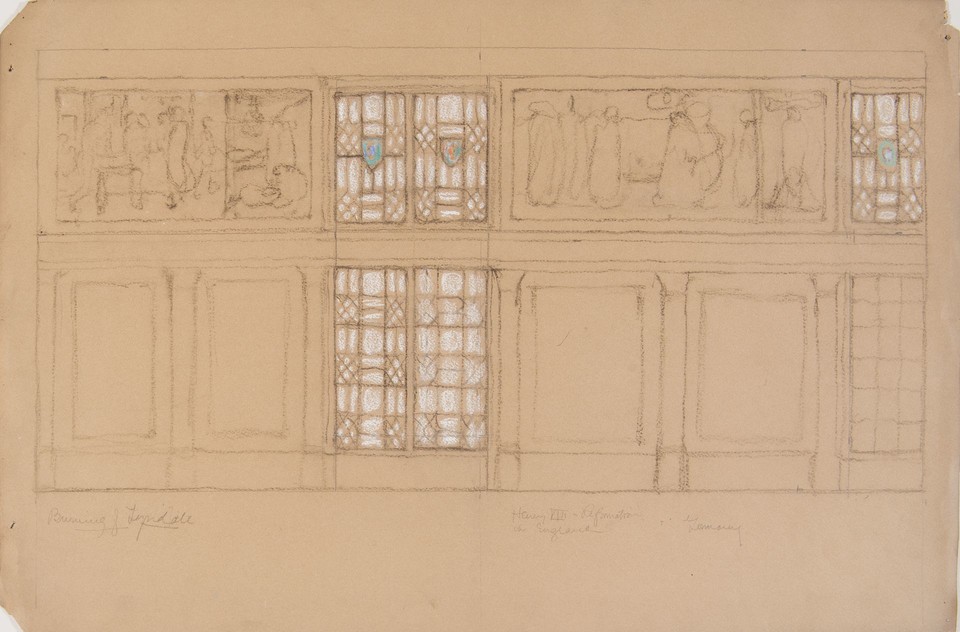

Composition study for "William Tyndale Printing His Translation of the Bible" and "Smuggling...into England," Panel 1, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Composition Study for "The Burning of the Books at Oxford," Panel 2, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

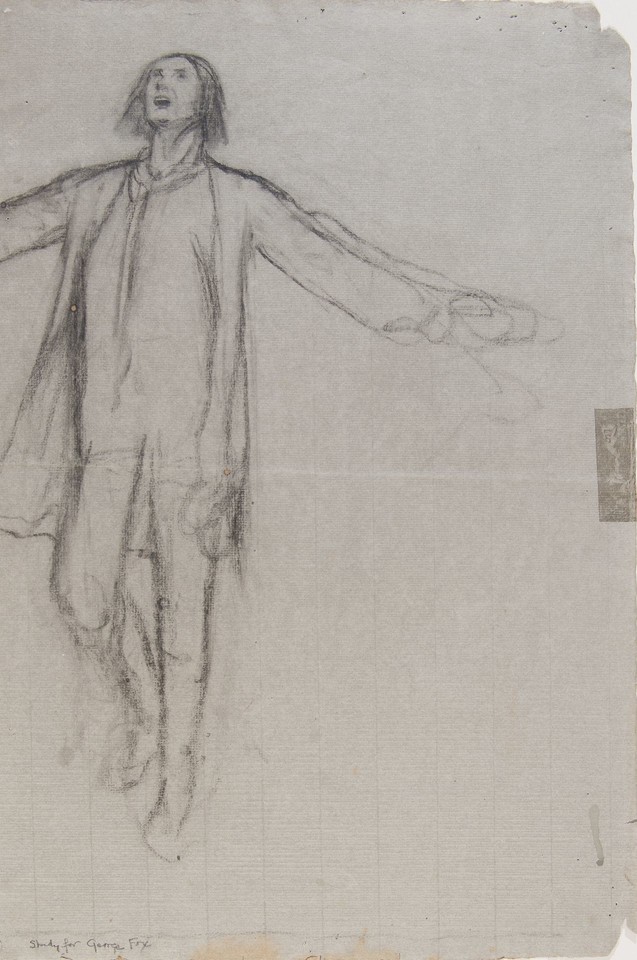

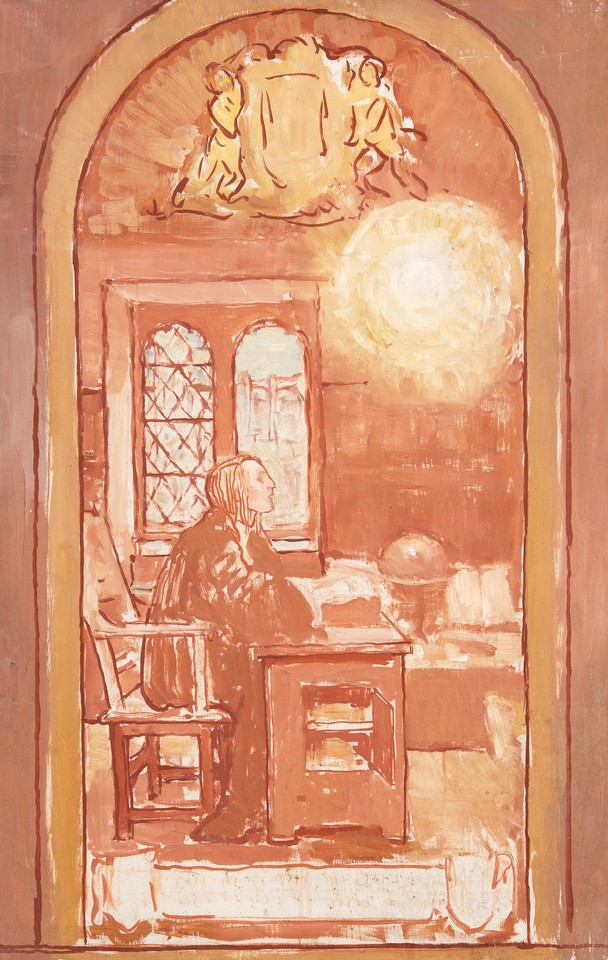

Study for "George Fox on the Mount of Vision," Panel 5, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "William Penn, Student at Christ Church, Oxford," Panel 6, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

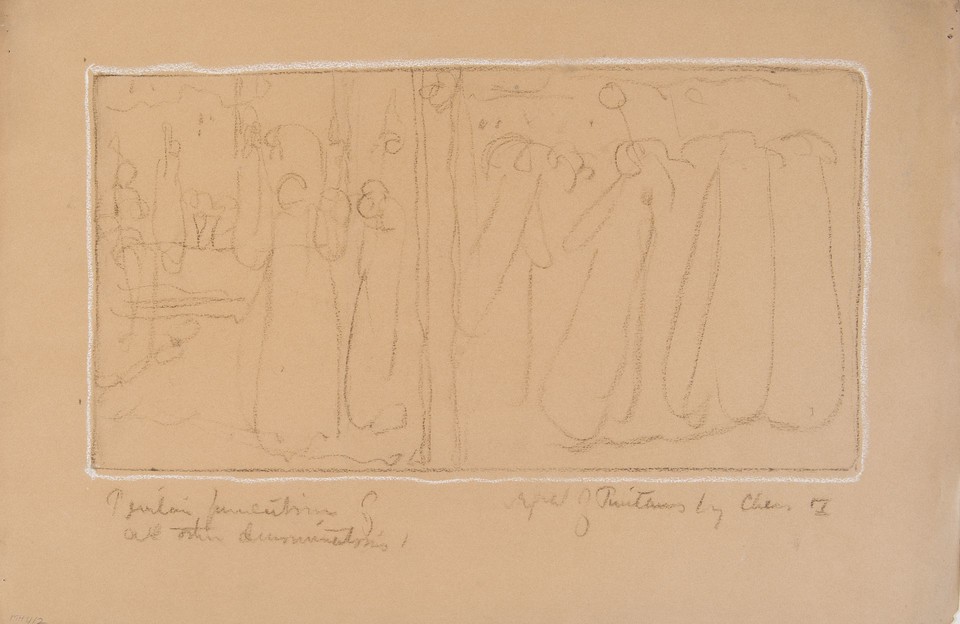

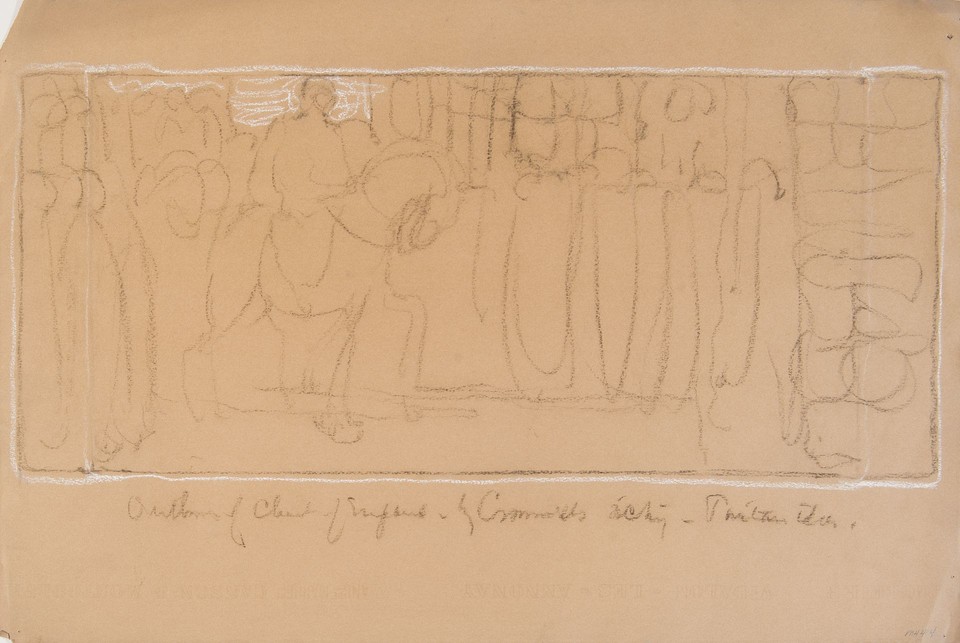

Composition study for "Culmination of Intolerance and Persecution in Civil War: Rise of the Puritan Idea," Panel 4, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Composition study for "Admiral Sir William Penn Denouncing and Turning His Son Away," Panel 8, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

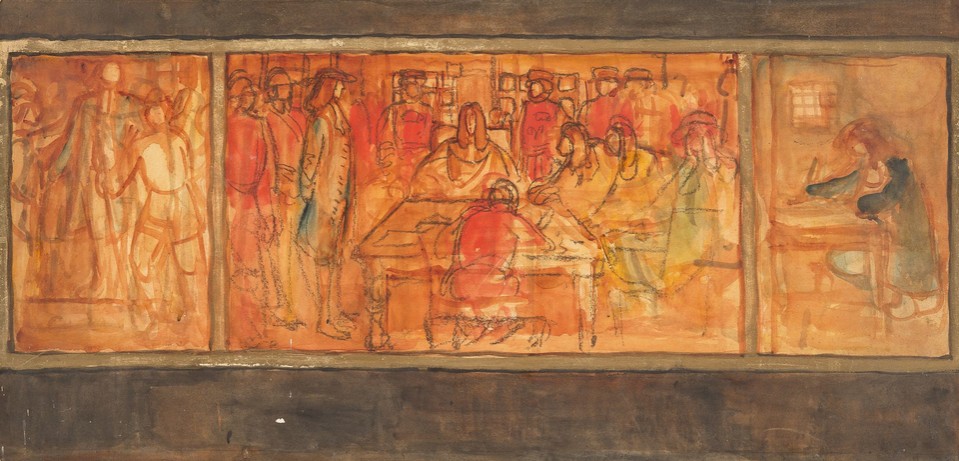

Composition study for "Penn's Arrest," "Examination," and "Writing in Prison," Panel 9, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Composition sketch for "Achievement of His Purpose: The Charter of Pennsylvania Receives the King's Signature," Panel 12, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "Penn Liberating Imprisoned Friends," Panel 10, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

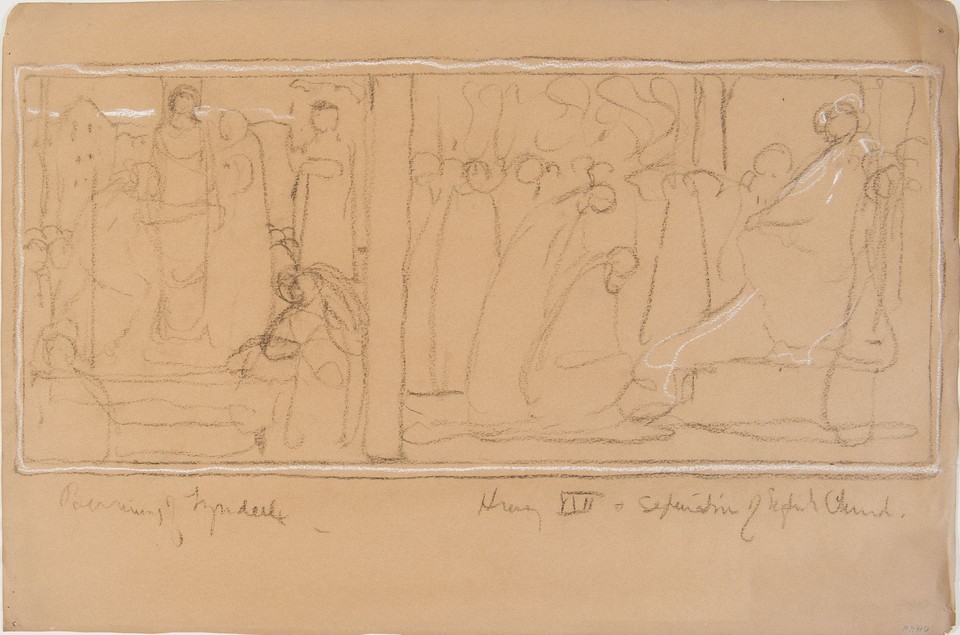

Composition study for "The Answer to Tyndale's Prayer" and "Anne Askew Refuses to Recant," Panel 3, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

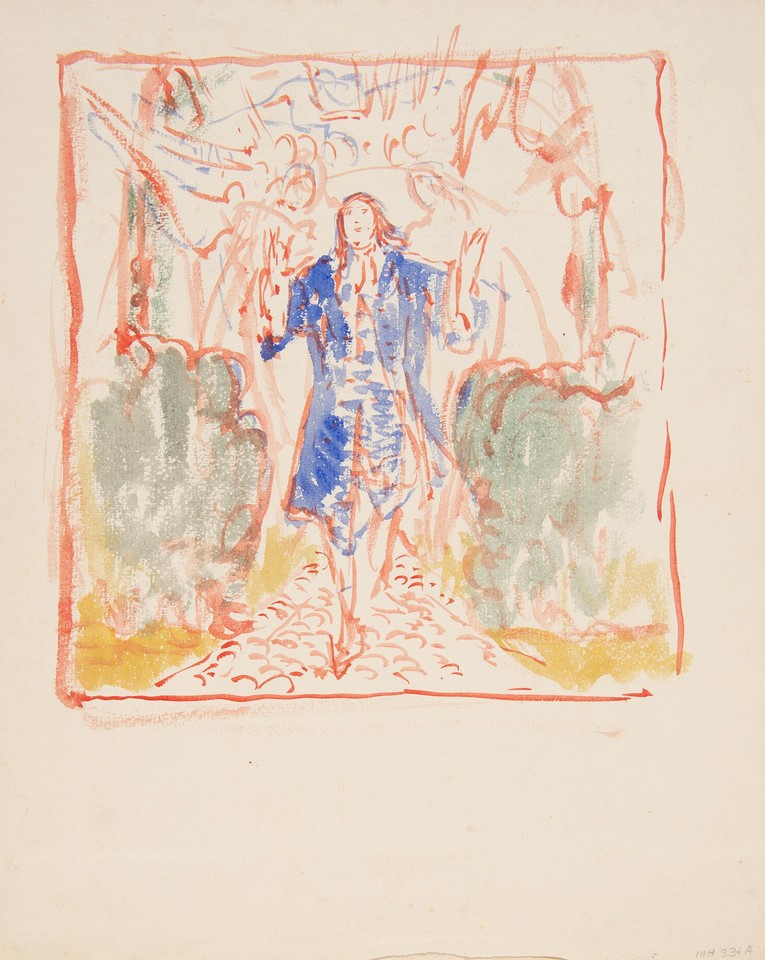

Composition study for "Penn Meets the Quaker Thought in the Field Preaching at Oxford," Panel 7, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "Penn's Vision," Panel 11, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Sketch for "Penn's Vision," Panel 11, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "William Penn, Student at Christ Church," Panel 6, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

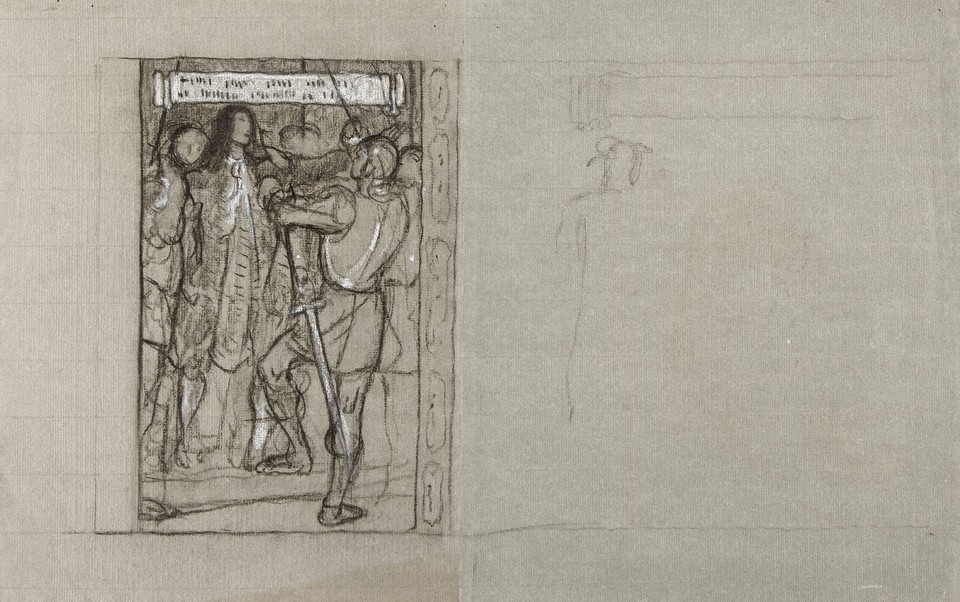

Study for "Penn's Arrest While Preaching at Meeting," Panel 9, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "Examination before the Lieutenant of the Tower of London," Panel 9, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

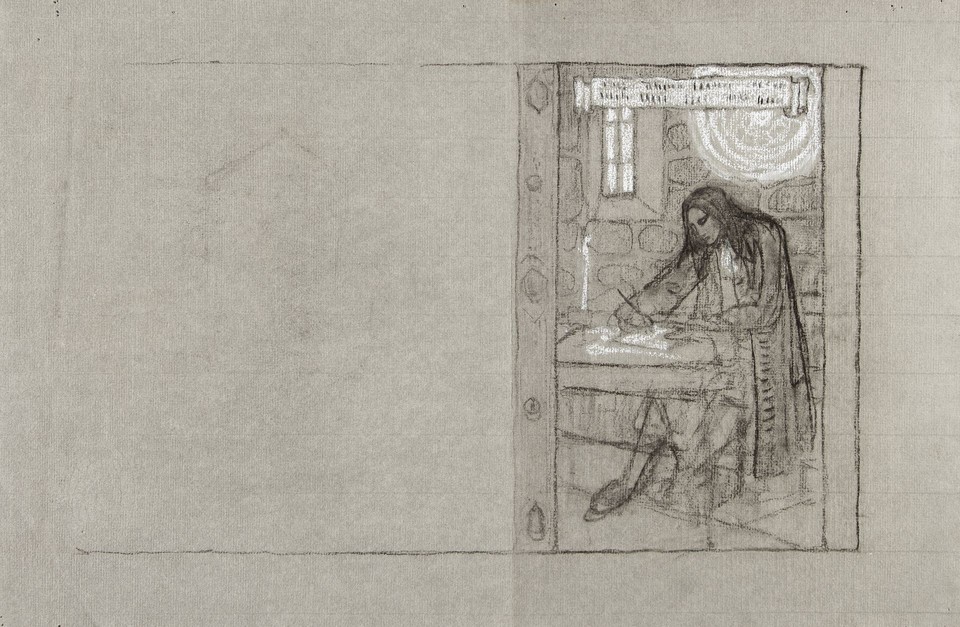

Study for "Writing in Prison (The Great Case of Liberty of Conscience," Panel 9, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

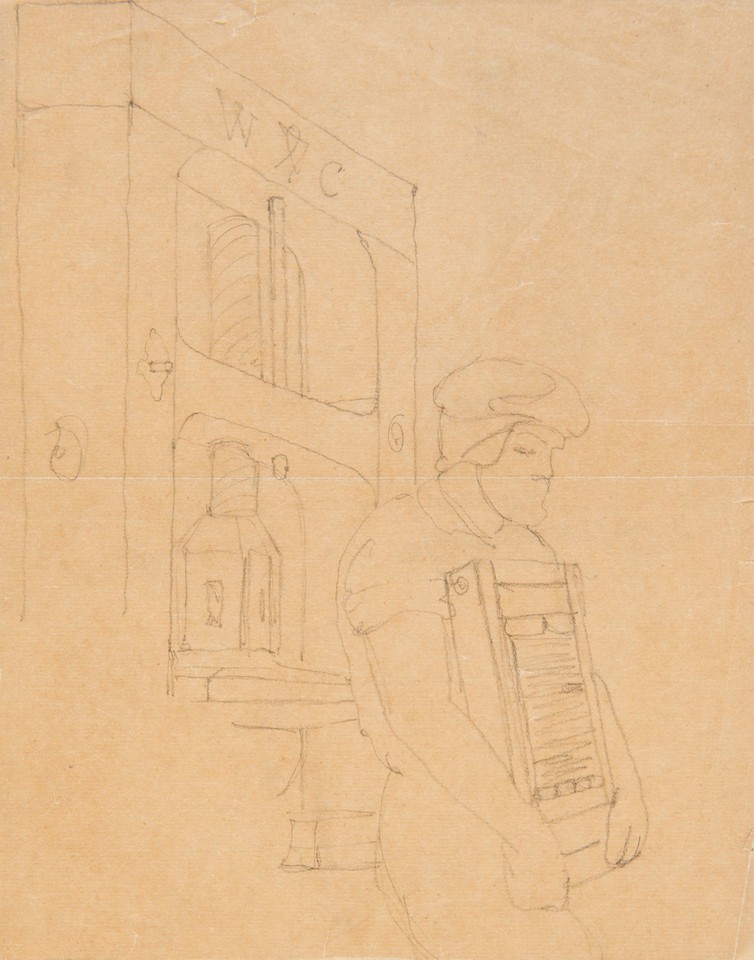

Study for "William Tyndale Printing His Translation of the Bible," from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Grand Executive Reception Room Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "George Fox on the Mount of Vision, 1652,” from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "Penn’s vision," Panel 11, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room Pennsylvania State Capitol[?]

Murals

View

Composition study for "William Tyndale Printing His Translation of the Bible" and "Smuggling...into England," Panel 1, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Elevation with composition sketches for Panels 1 and 2, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Composition study for the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study of man on horseback riding past crowd for the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "Penn Meets the Quaker Thought in the Field Preaching at Oxford," Panel 7, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

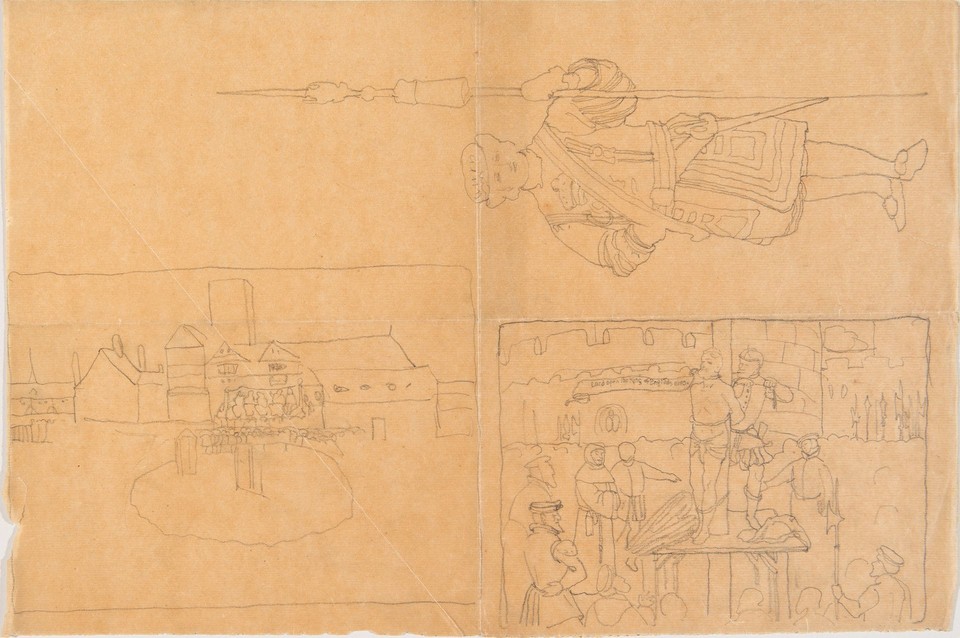

Studies for a Yeomen Warder (Beefeater); an outdoor scene with group of spectators in front of buildings; and the tying of Tyndale to the stake

Drawings and Watercolors

View

Composition sketch for Tyndale at the stake and English court scene, for the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for William Penn, "William Penn, Examination before the Lieutenant of the Tower of London," Panel 9, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

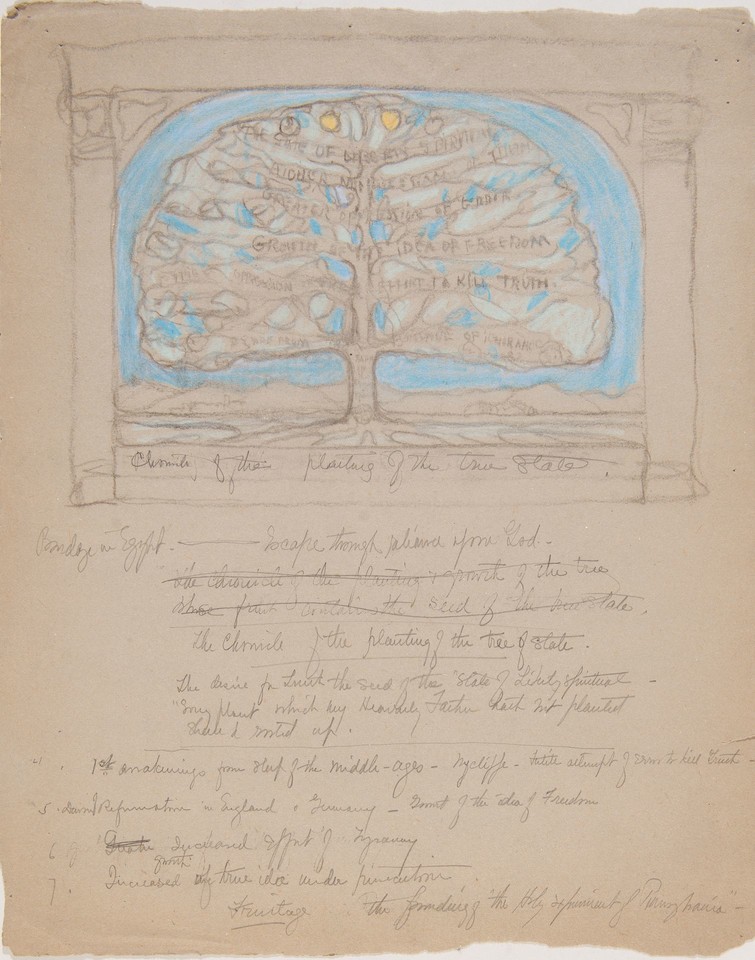

Study for “Chronicle of the planting of the true state,” Governor’s Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

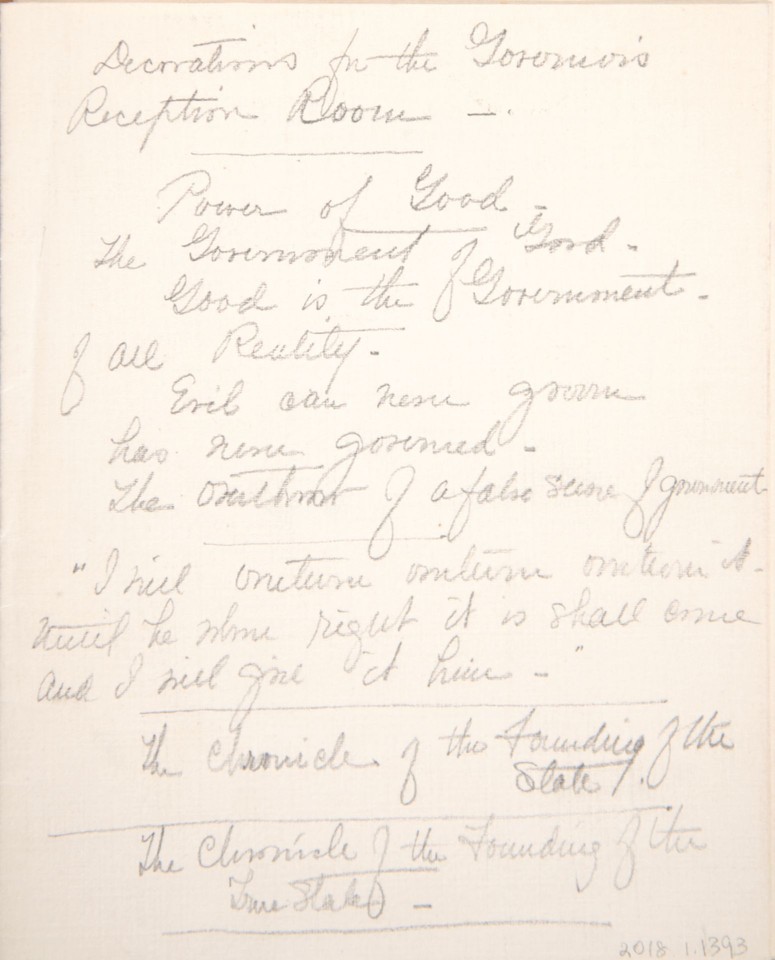

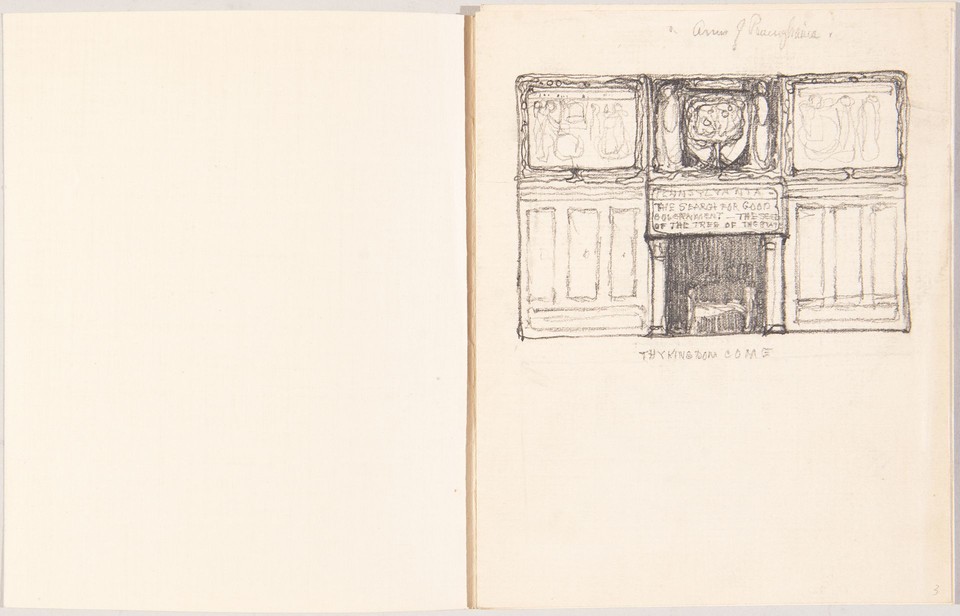

Study for "Arms of Pennsylvania" wall [Page 1] of "Decorations for the Governor's Reception Room" sketchbook

Murals

View

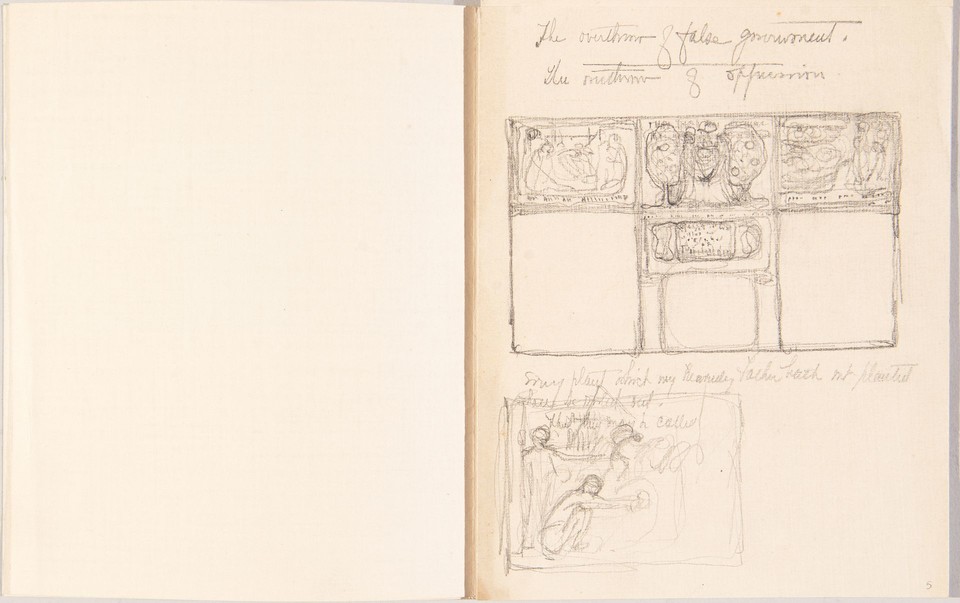

Elevation study for "The overthrow of false government / The overthrow of oppression" wall and panel detail [Page 2] of "Decorations for the Governor's Reception Room" sketchbook

Murals

View

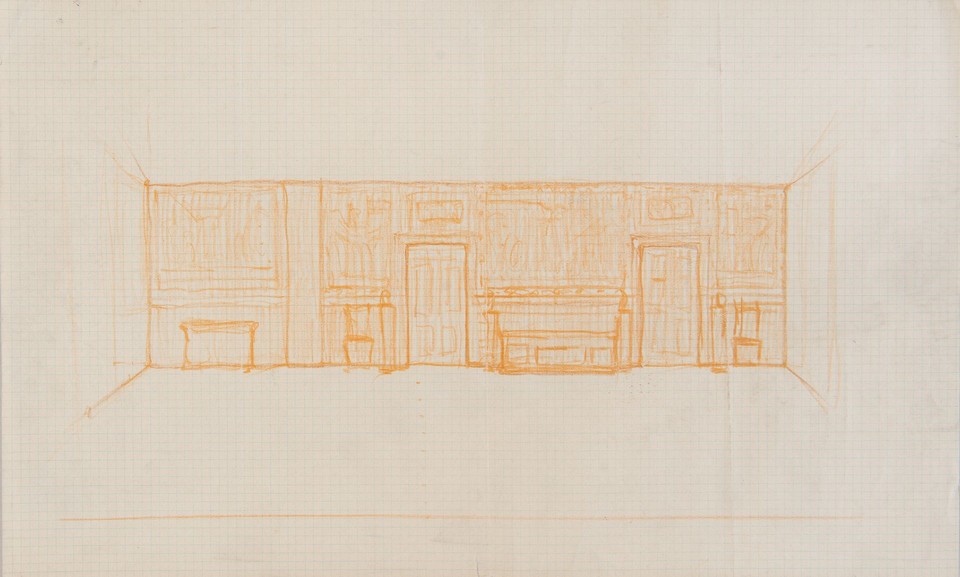

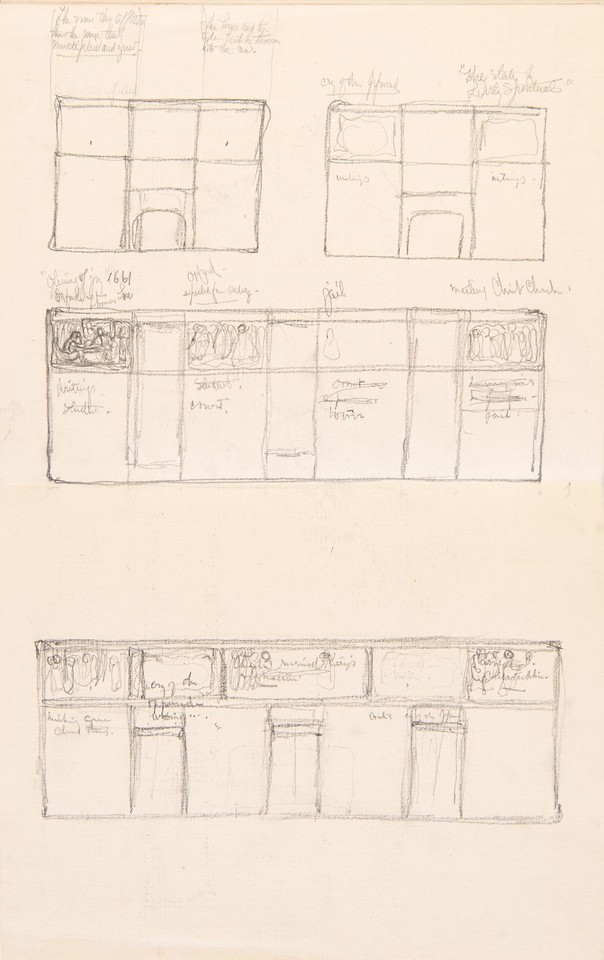

Elevation studies for two short and one long wall [left/top] and one long wall [right/bottom] [Pages 3 and 4] of "Decorations for the Governor's Reception Room" sketchbook

Murals

View

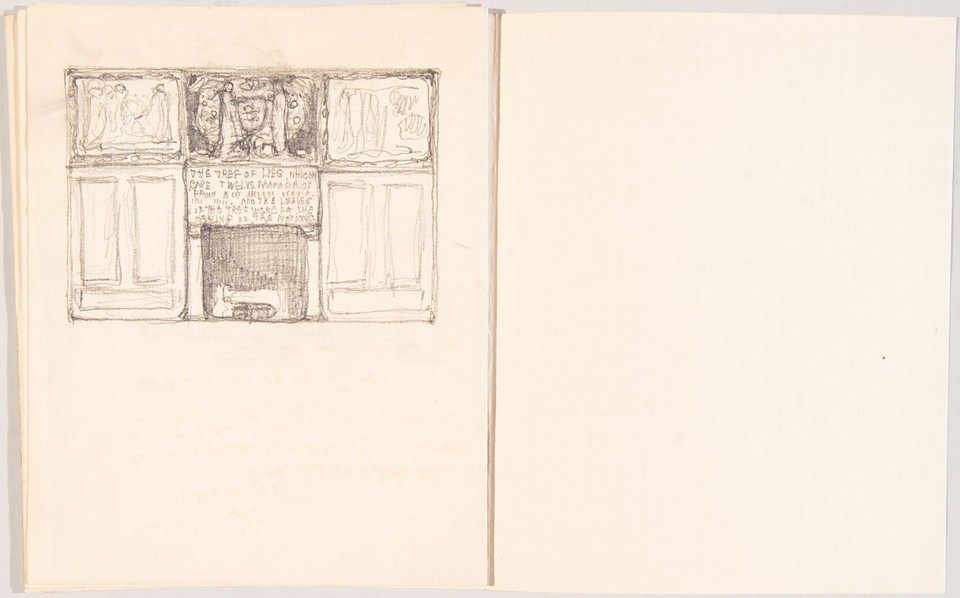

Elevation study for "Tree of Life" wall [Page 5] of "Decorations for the Governor's Reception Room" sketchbook

Murals

View

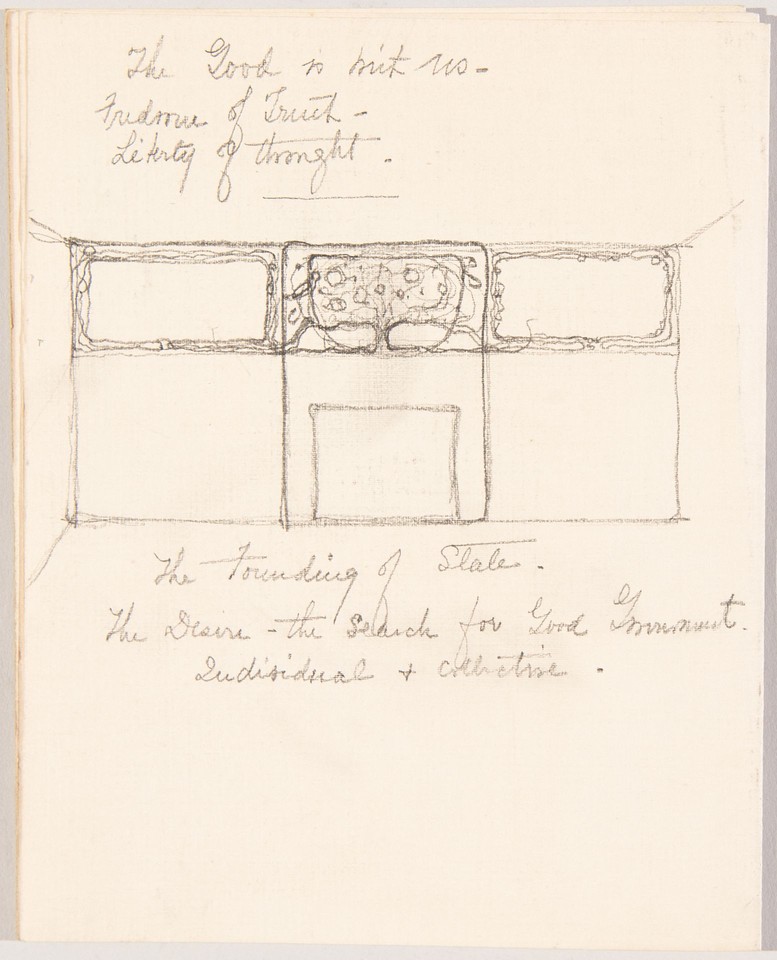

Elevation study for "The Good is with us / Freedom of Truth / Liberty of thought" wall [Back cover] of "Decorations for the Governor's Reception Room" sketchbook

Murals

View

Study for "William Penn, Student at Christ Church," Panel 6, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "Penn's First Sight of the Promised Land," Panel 13, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Composition sketch for the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Composition sketch for "Penn Meets the Quaker Thought in the Field Preaching at Oxford," Panel 7, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View

Study for "Penn Meets the Quaker Thought in the Field Preaching at Oxford," Panel 7, from the mural series The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, Governor's Reception Room, Pennsylvania State Capitol

Murals

View